Lucy Broadwood

Lucy Broadwood possessed extensive cultural interests but her main concern was for music. The composer and folk song collector, Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) described her as possessing a wide knowledge of literature and painting, and a great talent for music, as well as being an excellent pianist and most artistic singer. Mary Venables, a friend, referred to her intellectual powers and artistic capacity as singer, pianist, writer and folk song and folklore expert, and praised ‘the helping hand she was always willing to give to many young artists’.

Lucy was actively involved in London musical life. In her diaries, she described the musical evenings which she held at home in great detail. Dermod O’Brien, for example, wrote to thank her in 1901 for her hospitality and pleasant parties, ‘to say nothing of the education one gets in things musical at your flat’. She helped young musicians obtain engagements such as the baritone, James Campbell McInnes (1873-1945) and the composers Percy Grainger (1882-1961) and Graham Peel (1878-1937). The pianist, CA Lidgey, also in 1901, stated that ‘some fifteen engagements are to be traced directly and indirectly to yourself’. She arranged or wrote accompaniments to songs, one of which, ‘Jess Macpharlane’ an old Scottish air, enjoyed much success in the early 1880s.

Lucy Broadwood’s main claim to lasting fame is her work in developing the study of folk music. In 1915, Lucy wrote that her earliest musical memory was of sitting on her father’s knee whilst he sang her the Scottish folk song, ‘the wee little croodin’ doo’. Although her father did collect songs, the MSS of some of which are held by the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library, London, it is her uncle, the Rev John Broadwood (1798-1864), who is now regarded as the first pioneer of English folk song.

In 1847, John published Old English Songs, a collection of songs of Sussex and Surrey sung in the neighbourhood of Lyne that was noted for its fidelity in transcribing the songs exactly as performed; published version. The collection was reissued in 1889 as Sussex Songs with the tunes reharmonised by HF Birch Reynardson and with additional songs collected by Lucy Broadwood.

Already sensitive to folk song, in the early 1890s Lucy began collecting specimens from different parts of England. In 1893, in collaboration with JA Fuller Maitland, she published a collection under the title English County Songs which, according to Vaughan Williams, was the ‘starting point of the modern folk song movement’.

The following years saw the publication of the Rev Sabine Baring Gould’s Songs and Ballads of the West (1889-91) and Frank Kidson’s Traditional Tunes (1891). In 1898 the Folk Song Society was established to collect and publish ‘Folk Songs, Ballads and Tunes’ and Lucy was one of the founder members. Although it aimed ‘to save something primitive and genuine from extinction’, the Society was initially, in Ralph Vaughan Williams’ words, of the ‘dilettante and tea party order’. Lucy wrote a humorous poem describing the Society at this time, entitled ‘On WBS leaving the Committee of the Folk Song Society’. By 1904, the Society itself was at the point of extinction .

On 6 February 1904, Lucy met with the composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Cecil Sharp, a London music teacher who had come to folk song through his interest in traditional English dance tunes. Her diary records that they ‘discussed [the] Folk Song Society and made a scheme for reviving its dying embers’. Sharp and Vaughan Williams were elected members and Lucy became Secretary and editor of the Society’s Journal, retaining the latter post until 1926. The emphasis moved from dry academic debate to the active collection and dissemination of folk song and the Society took off.

Important issues of the Journal include a number composed entirely of examples from Lucy’s own collection of songs from Sussex and Surrey; Miss Tolmie’s collection of Gaelic Songs; and a further collection of songs from Surrey and Sussex collected by Lucy, George Butterworth and Francis Jekyll. Lucy also published a second collection, English Traditional Songs & Carols, in 1908.

It is clear from her correspondence and from the comments of Vaughan Williams that Lucy came to disapprove of Cecil Sharp: ‘he puffed and boomed and shoved and ousted, and used the Press to advertise himself’. When he founded the English Folk Dance Society in 1911 she did not give it her support. She handed over the editorship of the Journal to Frank Howes in 1926 but continued to contribute material. She remained a member of the committee and when Lord Tennyson died in 1928 she was elected president.

Mary Venables, describing aspects of Lucy’s personality, commented on ‘the sincere and whole hearted satisfaction’ which Lucy felt at having adhered to spinsterhood in spite of ‘many pressing opportunities of quitting it’, and also her great ability in all writing games and in making comical drawings and delightful sketches and rhymes. But another side of her character was reflected in her interest in spiritualism and the interpretation of dreams; and in her serious verses which ‘came from the depths of her nature which often appeared to be struggling against sadness and pessimism.’ Moreover Mary wrote that Lucy ‘dreaded the development of modern science, abominated the sound of aeroplanes and hated to look up at them’.

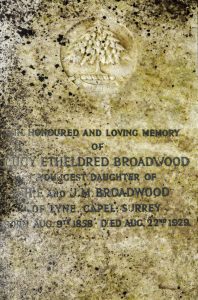

Lucy was buried at Rusper and there is a fine memorial to her in Rusper church.

Copyright Surrey History Centre.